New Paper: Geometric Template Placement with Binary Trees

Matched Filtering on Curved Manifolds

In gravitational wave astronomy, the optimal strategy for detecting signals buried in Gaussian noise is matched filtering. This requires a discrete set of waveform filters, or a Template Bank, \(\{h(\vec{\theta}_i)\}\), that covers the continuous parameter space of compact binary mergers. The effectiveness of a bank is measured by the mismatch—the fractional loss in signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) due to the discreteness of the grid.

Constructing these banks is a problem of differential geometry. The parameter space \(\mathcal{M}\) (masses, spins) is a Riemannian manifold endowed with a metric \(g_{ij}\) defined by the inner product of the waveform derivatives. The distance between two points on this manifold represents the loss in SNR:

\[ 1 - \mathcal{M} \approx g_{ij} \Delta \theta^i \Delta \theta^j \]

Because the metric depends on the coordinates (the manifold is curved), the local density of templates required to maintain a fixed minimal match is proportional to \(\sqrt{|g|}\). In the low-mass regime, the curvature is high, requiring dense placement; at high masses, the manifold flattens out. Historically, the field has relied on stochastic placement—randomly sampling points and rejecting those too close to existing templates. While robust, this is computationally expensive (\(O(N^2)\) without heuristics) and produces an unstructured, amorphous set of points.

Recursive Decomposition

In our paper, A binary tree approach to template placement, we propose a deterministic, geometric alternative: Treebank. [1]

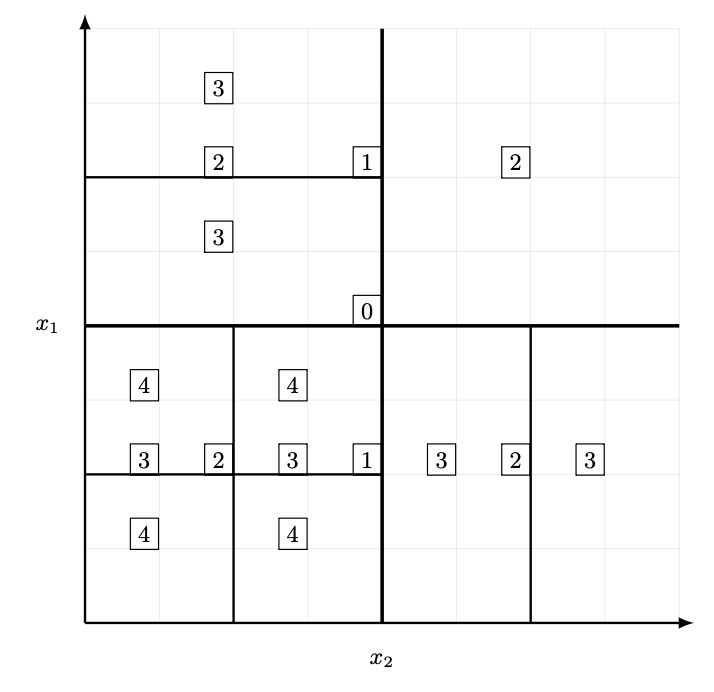

We approach the problem as a recursive binary space partitioning task. We initialize the search space as a single hyper-rectangle and recursively subdivide it based on the local Riemannian geometry. For a given hyper-rectangle, we calculate the metric \(g_{ij}\) at the centroid and estimate the number of templates \(\mathcal{N}\) required to cover its proper volume.

The algorithm proceeds as follows:

- Metric Evaluation: Calculate the proper length of each edge of the hypercube using the local metric.

- Bifurcation: If \(\mathcal{N} > 1\), split the hypercube in half along the dimension with the largest proper length.

- Recursion: Repeat the process for the resulting child nodes.

- Placement: When \(\mathcal{N} \approx 1\), the recursion terminates, and a template is placed at the geometric center.

Geometric Structure and Efficiency

This approach effectively translates a physics problem—covering a signal manifold—into a classic computer science structure, the \(k\)-d tree.

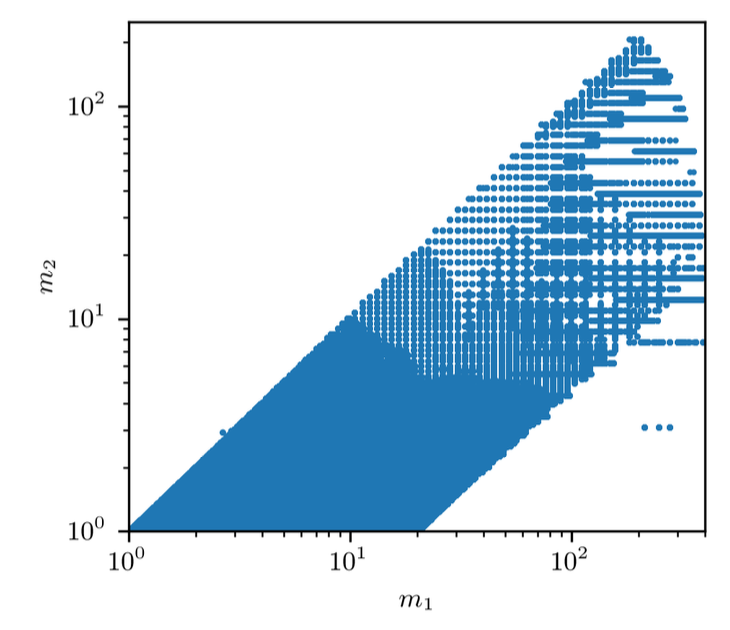

The computational gains are significant; we generated a bank suitable for Advanced LIGO (covering component masses \(1 M_\odot < m_{1,2} < 100 M_\odot\)) in approximately 24 CPU-hours, a task that can take days with stochastic methods.

However, the primary advantage is structural. Stochastic banks are unstructured point clouds. The Treebank algorithm partitions the parameter space into non-overlapping hyper-rectangles, where each template “owns” a specific, well-defined volume of the physical parameter space. This structure simplifies downstream Bayesian inference and population modeling, as numerical integration over the parameter space becomes a summation over defined Euclidean volumes weighted by the local metric.

We produced a bank of \(\sim 2 \times 10^6\) templates. While the geometric constraints force a slightly higher number of templates than stochastic limits to achieve the same minimal match, the average match is higher, potentially improving the overall detection efficiency of the search pipeline.

You can view the code for this project here: gwsci-manifold